| |

|

|

| Many thanks to Matt Monaco and to Prof. McKnight who teaches Music History at the University of North Carolina at Asheville. |

| |

|

Ludwig Van Beethoven was born into a musical family in Bonn, Germany in 1770. The son of a court musician, his talent for piano was evident at a young age as he gave his first public concert at the age of 8. His father recognized his talents and wanted to take advantage of his talented young son in a manner similar to Mozart's father Leopold (McMillian, 1). At the age of 17, Ludwig entered the employment of the court in Bonn and spent time studying with Hadyn and Mozart. Neither of these relationships were particularly fruitful for Beethoven as he had a strong distaste for many of the more traditional ideas embodied by his two teachers (McMillian, 1-2). Beethoven composed from life and as a result, his music such as the Missa Solemnis is very indicative of his state of mind at the time it was composed. For this reason, Beethoven's musical works are simply divided into three periods: the early, the middle, and the late, each period strongly reflecting the evolving life of the composer, both on and off the staff. He is also known as the father of Romanticism and a key player in the transition between the classical and the genre he is said to have fathered (McMillian, 1-2). Shortly after his move to Vienna in 1792, Beethoven entered a period of composition, primarily for piano, that would later be known as early. During this time, he used his virtuosic skills and the accidental misspelling of his name "Van" as "Von," denoting aristocratic birth, to gain the favor of the nobility in Vienna. While in Vienna, Beethoven composed many excellent pieces, most of them approximating and assimilating his vision into the classical style. The most famous example this style in the early period is the Pathetique Sonata, Opus 13, composed in 1798. (McMillian, 1) (Britannica CD). The year of 1800 showed the world a changed Beethoven. No longer bound by the idioms of his classical predecessors, Beethoven began expanding into unusual forms and tonalities to increase the potential for expressiveness. This pursuit of expressiveness would be the hallmark of the Romantic era and was to be actively pursued by Beethoven's most famous predecessors such as Franz Liszt, Hector Berlioz, and Felix Mendelssohn. The greatest opus of Beethoven's newly-found Romantic vision, completely grandiose in form, harmonic texture, and range of tonality, is his 3rd Symphony, Opus 55 (1803), otherwise known as the Eroica (Heroic) Symphony. For this reason, many refer to this period, despite it technically being the middle period, as his Heroic period. After Eroica, Beethoven continued to expand his tonal palette and imagination, creating masterpieces in almost every conceivable genre including his lone opera Fidelio (1803-1805) and the 5th Piano Concerto (Emperor), in 1809. (McMillian, 3) (Drabkin, 1-5) (Encarta 2000). The personal history that surrounds Beethoven's composition of Missa Solemnis is not a happy one. Beethoven began the work in 1819 with the intent for it to be performed at the ceremony where Rudolph, Archduke of Austria, was to be made Archbishop of Olumütz in Moravia. Rudolph, the younger brother of Franz II, who was the Austrian emperor that helped secure a large annuity for Beethoven in exchange for his continued residence in Vienna, was a student of Beethoven at the time. Rudolph would become Beethoven's most generous and consistent patron over the fifteen years in which he received lessons in piano and composition from Beethoven. Missa Solemnis, most historians note, is as a rare instance in which a clear connection can be made between an event in Beethoven's life and a composition of a major work. Beethoven wanted to devote himself wholly to this project and as a result postponed the composition of a 9th symphony as well as a piece that would later be known as the Diabelli Variations. Despite his efforts, the growing size and complexity of the piece as well as personal problems such as the battle for the custody of his young nephew Karl prevented him from finishing the piece by the deadline date for Rudolph's installation, which was March 9, 1820. With the passing of this date, the pressure was off and Beethoven took time to work on other projects while continuing to revise his mass that was finally submitted for presentation in the spring of 1823. (Drabkin, 1-5) (Britannica CD). Beethoven began the composition by translating the entire Mass Ordinary from Latin into German. He then made minor adjustments to the text to allow for greater musical expressiveness and added annotations to further his understanding of the text. Beethoven held his own personal interpretation of the text above the previous conventional interpretations and composed music to support his ideas about the text. Most of the piece was sketched in small notebooks that could fit in the composers pocket so he could document musical inspiration while he was away from home (Drabkin, 14- 15). The religious inspiration for the Missa Solemnis is a topic of great depth and debate. While it is clear that Beethoven did have a belief in a supreme power, it is also prudent to note that he did not attend church regularly or appear to be a devout member of any church. This said, Beethoven did careful research over the period of one year to insure that his setting of the text would accurately reflect the key elements of the church style within his own distinctive and expressive style. There was also justified concern at the time as to whether or not the evolving piece could function in a church setting due to its growing length and the sheer numbers of musicians needed to perform it (Carlos, 2-3)

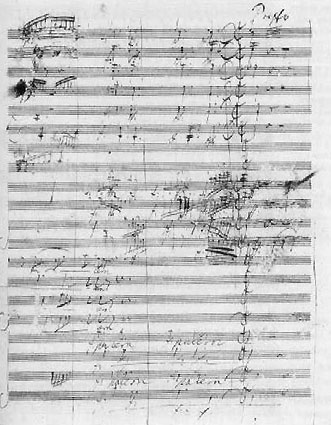

A page from the Original Score of Missa Solemnis The texts used in the mass were of great importance to Beethoven who carefully selected and preserved them almost exclusively throughout the composition. While Beethoven's primary purpose in composing the Missa Solemnis was for performance as the mass for a particular religious event, he also believed that it could and should be performed outside of a church setting. Emphasizing the capacity of the music alone, Beethoven wrote: "My chief aim was to awaken and permanently instill religious feelings not only into the singers but also into the listeners." Beethoven sought to bring religious inspiration to the performers and the audience, making the words and spirit of the text accessible to all. Through this piece, he was able to express very universal religious ideas in a manner that could not have been accomplished by the words alone (McMillian, 3) (Young, 49-53). The Missa Solemnis features the following instruments: Soprano, alto, tenor, bass choir, soprano, alto, tenor and bass soloists, 2 flutes,2 oboes,2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, double bassoon, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, drums, percussion, and organ. The grandiosity of Beethoven's arrangements required such a large group of musicians provided yet another problem for performance of the piece in a church setting. The piece itself is divided into five sections. They are the Kyrie, the Gloria, the Credo, the Sanctus, and the Agnus Dei (Grout 536-537). The Kyrie, which begins the mass, is set in cut time and is in the key of D. This section is marked "Mit Andacht," or "with devotion" and is focused on the concept of holy trinity with two verse-long divisions. In the first verse, the text "Kyrie eleison" is repeated in a call and answer fashion between the choir and the soloist. The choir in this case is said to represent the people and the soloist as the priest. This verse, which translates literally to "lord, have mercy upon us," is repeated three times as the music swells as the lyric is sung and then returns to relative quiet before the next intonation (McMillian, 5). The second verse of the Kyrie, also known as the Christe, modulates to the relative minor and is performed in 3/2 time, giving this section a rhythmically restrained feeling compared to the first verse. This idea was one of many elements of the Beethoven Solemnis borrowed from previous generations of mass composers in an effort to make his mass more traditional. In furthering the symbolism of the holy trinity, this verse emphasizes the interval of a 3rd, and usually performed by one of the soloists. (McMillian 5) (Drabkin, 28-30). At the conclusion of the Kyrie, the music modulates back to D major briefly before moving to the subdominant key of G major to setup the final resolution in D major. This resolution is the final element of piece in a ternary form, which can be viewed as a simple ABA'. (McMillian, 5). The Gloria in D contains two allegro movements in ¾ time that move through a variety of textures and moods to convincingly express the sentiments of the composer. Expression is king in this part of this mass in which all statements are addressed to God. It is also notable the extent to which Beethoven added drama to the Gloria with dynamics, key changes, and a winding progression of ideas that might be identified as form. These elements unfortunately contributed to this section's inappropriateness for performance in church (McMillian, 5) (Drabkin, 37-42). The only part of Beethoven's masterful mass without a tonal center of D major is the Credo in Bb major, a major third above the tonality of the rest of the piece. The Credo spans the most time and contains the longest text of the five sections. It was also the most difficult for Beethoven to set to music. The credo is divided into four sections; two allegros in 4/4 and 2/2 respectively, an expressive adagio in ¾ and an allegretto in 3/2 time. A single theme is introduced at the beginning and unifies the piece as it is performed in a fugal style by each section of the choir. Beethoven makes use of modal structures in certain parts of the work, as they were believed to represent the supernatural (McMillian, 5) (Drabkin 52-53). The Sanctus is focused strongly in D major. This tonality signifies the joyful nature of hope and serenity implied by the text of this section: "Pleni sunt caeli et terra Gloria tua!" This element of the Beethoven Solemnis is divided into three main sections: an adagio in 2/4, a praeludium in 6/8, and an andante in 12/8. This marks the first appearance of compound meter thus far in the piece. As in his earlier Mass in C, Beethoven's Sanctus also includes the Bendictus which is preceded by a beautiful prelude apparently adapted from a composition written by a teenage Beethoven as his days as an organist in Bonn (Drabkin, 66-67, 76-77). "O Lamb of God, that takest away the sins of the world, have mercy upon us, grant us peace," is the literal translation for the last movement of the Missa Solemnis. The Agnus Dei begins in b minor and is the only section of the mass to remain in a minor key throughout, switching between b minor and e minor during the beginning and middle sections of the work. This is the most devotional and somber section of the entire mass. Towards the end of this section, Beethoven elects not to repeat the entire verse and instead emphasizes his desire for peace by repeating the phrase "dona nobis pacem" in a Sonata-Rondo form. It is during this section that he adds the famous war march and takes the most creative liberties with the text in changing the order of the words and repeating certain phrases to further his own interpretations of the text (Drabkin, 83-85). Despite its lack of theoretical recognition at the time, Beethoven's use of sonata form throughout the mass is evident. In Beethoven's later works, "Form is a function more of space and design than of tonality.the dominant is no longer ex officio the agent of tonal opposition." Another instance of the use and expansion of the Sonata form is in Beethoven's blurring of the boundary between development and recapitulation in both the Benedicuts and the 'Dona sections of the work (Drabkin, 19-20). Harmonically, the use of keys separated by thirds is common throughout the Missa Solemnis as Beethoven used shared tones for common-tone modulations. One example is the use of the note F#, scale degree 3 in D major, to join the Kyrie with the Christe which begins with F# as scale degree 5 in the relative minor (B minor) and ends with F# interpreted as scale degree 1 in F# minor. Many musicologists also agree that the Beethoven Solemnis is antithematic, perhaps another attempt by Beethoven to ignore and/or refute the conventions of the time (Drabkin 21-23). The religious significance of the Missa Solemnis is an issue of great importance as Beethoven's spiritual beliefs were somewhat unclear despite his Catholic upbringing. Many believe that he used his Mass in D to show disdain for tradition and authority just for the sake of tradition and authority. He believed that the social conventions of the time that suggested all mortals follow the leadership of a "higher" power was in need of some revision. For this reason, Beethoven composed very few sacred pieces. This distaste for ceremony was also evident in the half-heartedness that ran through previous religious works composed during his heroic period such as Christus am Olberge (The Mount of Olives) and the Mass in C (1807). The piece was a turning point for Beethoven. Missa Solemnis was used to give definition to his religious/spiritual beliefs and to "come to terms with god" during a time of spiritual crisis. (Drabkin, 4-6)(Carlos, 3). The historical significance of Beethoven's setting of the Mass Ordinary is often addressed in terms of comparable works of the time period. Beethoven was heavily influenced by Handel's Messiah in terms of the choral writing and most specifically in the "Gloria in excelsis Deo" section of Beethoven's Gloria. Others site even further instances of Handelian concept throughout the piece. The significance of this work in terms of what followed it has been noted by Augsberg Kapellmeister Wilhelm Weber who found several references to the Missa Solemnis in Beethoven's next piece that was the 9th Symphony. In considering the analysis of this piece, it is essential to note Beethoven's subtitling at the head of the score that read: "Von Herzen - möge es wieder - zu Herzen gehn!" This sheds some light on the enigmatic nature of the piece and its lack of unity in form and content. These traits were viewed as typical during Beethoven's late period as an attempt to deny the listener objective interpretation and arrive at greater personal meaning through this interpretation (Drabkin, 3-6). The Mass in D known by many as Missa Solemnis or rarely the Beethoven Solemnis was a masterpiece of religious expression, interpretation, and musical innovation by Beethoven. Missa Solemnis began the first religious work of this size created and Beethoven did so in a manner completely indicative of his highly personal style. While the composition was originally intended to be performed in segments with only the Kyrie and the Gloria performed in consecutive order, the mass is still performed today, although almost exclusively in a concert setting rather than a church service. While it is almost unbelievable that a man in such dire straits could put together a piece of this quality, it is clear that the tumultuous five years of his life that yielded this composition were most definitely worthwhile. |

| |

|

|

||||||||||||||||